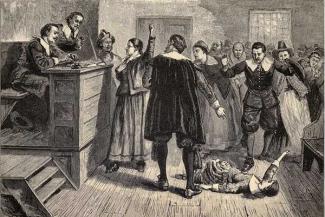

“It begins in the house of a minister,” says Kathleen M. Brown, the David Boies Professor of History. Samuel Parris’ 9-year-old daughter, Betty, begins to exhibit strange symptoms. The doctor watched her violent fits and suggested supernatural causes. Stranger still, the illness seemed to be contagious. Parris’ 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams, was beset by fits, followed by two others: 12-year-old Ann Putnam and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard. By March 1, 1692, three women were accused of witchcraft: Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba, an Indigenous woman from Barbados, who was enslaved by Parris. Thus began the Salem witch hunt, one of the stranger episodes in American history. By its close, 10 girls and young women claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft, resulting in the deaths of 20 people, one of whom was accidentally killed during torture.

One of the reasons that the Salem witch trials are “still very fascinating to people in the present day,” says Brown, is that 17th-century Puritan New England was a highly codified patriarchal society. “This is not a society that ordinarily provides girls and young women with speaking roles.”

The young women seem to “be on the same page for reasons that nobody really understands, even to this day,” Brown says. The young women may have dabbled in fortune telling to ease their anxieties about their marriage prospects, which determined their futures along with their financial stability. Several of the women were servants and nieces, who may have experienced heightened anxiety about dim marital prospects due to lack of money and family connections. Many of them were orphaned during skirmishes with Native Americans on Massachusetts’ northern frontier and were not only displaced but had recently experienced bloodshed, loss, and trauma, Brown says.

Violence occurring on the northern border created a sense that the colonists were losing control, Brown says. People were dying. The Puritan leadership was unable to “keep residents of the larger settler community safe from Native Americans,” who the Puritans often associated with the devil, Brown says. The leaders of the colony, all Anglo-Saxon men used to being in power, used to protecting their families, and charged with a sense of religious purpose, were feeling “that they’re impotent in the face of this challenge from Native Americans, who may be working through the power of the devil to afflict the larger colony,” Brown says.

The year 1692 was one of general unrest. “Just to make it even more complicated, part of the political conflict that’s occurring on the brink of the Salem outbreak involves a loss of autonomy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” says Brown. In 1689, the British crown inserts its own appointee as colonial governor, and the colony ejects the appointee on the grounds that he doesn’t represent their Puritan leadership.

Meanwhile, traditional Puritan leadership, along with the population of Puritans, “has been shrinking,” Brown says. By the “1690s, New England is a much less Puritan place than 1630s.”

While lots of explanations exist as to why something happens in 1692, “it seems that no explanation really gets at all the factors,” Brown says. “Why are young girls and young women feeling that they’re possessed by the devil and are cursed and tormented by older women and men in the community?”

Read the entire story HERE